Local Food Hubs Help Small Businesses Succeed

David Klingenberger, chief fermenting officer of The Brinery, is taking a break between veggie slicing and kimchi packing to enjoy lunch with his staff in their shiny new digs at the Washtenaw Food Hub, a new aggregation, processing and distribution center located just outside of Ann Arbor. “I was at a small space was that was maxed out,” says Klingenberger. “This place really lined up with what I wanted to do.”

The Brinery is the hub’s first anchor tenant. The brainchild of Tantré Farms owners Richard Andres and Deb Lentz, the business launched in 2012 on the site of an old agricultural chemical storage facility in Ann Arbor Township. Over the last year, Andres, Lentz and manager Kim Bayer have been putting in sweat equity to build their shared dream of a place where local farmers and local markets can come together. “Eventually what we want to do is restore this entire property so that it’s a beautiful, educational destination for people in the community,” says Bayer.

A food hub is defined as “a centrally located facility with a business management structure facilitating the aggregation, storage, processing, distribution and/or marketing of locally or regionally produced food products” by the USDA, which recently announced a $78 million investment in local farmers and food hubs.

The model grew out of explosive growth in demand for local food and food products over the last decade, says Erika Block, founder of Local Orbit, an Ann Arbor–based technology company that offers a cloud software platform linking growers and buyers. That demand resulted in a glut of farmers’ markets, which are nice for consumers but rarely cost-effective for farmers.

“I think we have 8,400 farmers’ markets in the state now, but no one has ever shown that the aggregate sales have increased in proportion to the number of markets,” says Block. “What happens is the farmers get diluted. Farmers are starting to recognize that having a mix of farmers’ markets combined with wholesaling for local distribution builds a stronger business.”

According to the 2013 National Food Hub Survey, more than half of food hubs opened within the last five years, and 75% are within metropolitan areas.

“The idea is that right on the edge of town you have this place that brings together the rural-to-urban interface,” says Andres. “Folks that want to do value-added processing can bring in raw materials, and people who are interested in those processes can having meaningful participation to learn about how food is made.”

Bringing rural and urban together can present challenges, according to Sally Elmiger, a community planner with Ann Arbor–based Carlisle/Wortman Associates. Elmiger worked with Ann Arbor Township to develop a zoning ordinance allowing the Washtenaw Food Hub to operate while maintaining rural character. The ordinance restricts sourcing to farms located within 100 miles of the facility.

“The food hub folks were great to work with. They were there to explain what they were doing and how they do it,” says Elmiger. “And that really enabled the development of an ordinance that works for the food hub and the neighbors.”

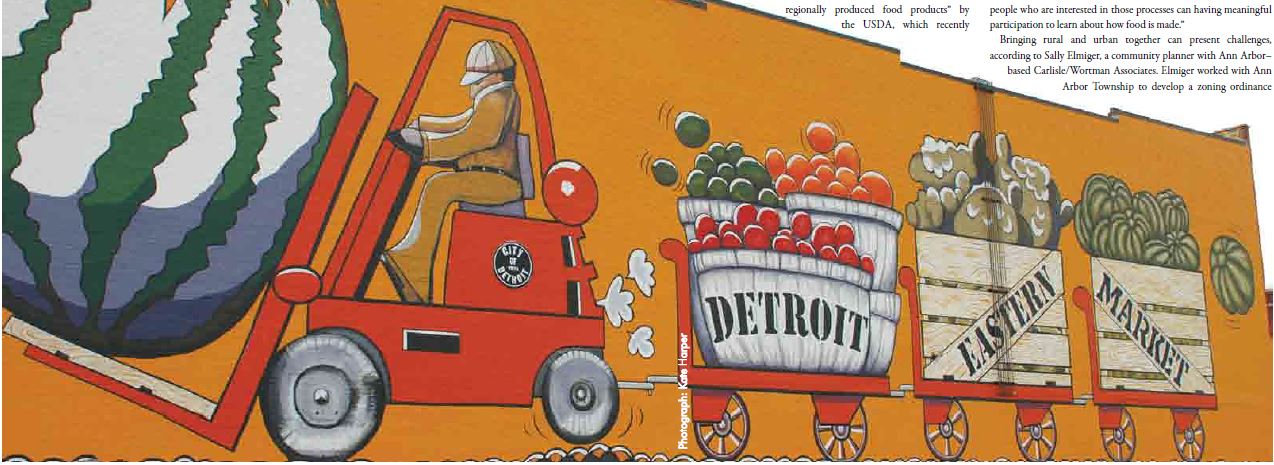

While the term is new, it describes something that’s been happening for more than 120 years at Detroit’s Eastern Market, according to Christine Quane, wholesale market coordinator for Eastern Market Corporation. “My role is creating more connections between growers and end-users,” says Quane. “I’m trying to get more Michigan produce in more distribution chains, to get more Michigan produce on more plates.” Quane works with growers, chefs, institutions and restaurants to make connections and shorten the distribution chain.

Helping farmers build the capacity for local sourcing is critical. “There’s still a supply issue, and that’s been an ongoing challenge for quite some time,” says Yvette Berman, co-founder and CEO of Harvest Michigan, a Rochester Hills–based food hub focused on the business-to-consumer market. “I can get conventional produce anytime, but local, organic produce is harder to come by.”

To address the supply side, Washtenaw Food Hub is working with nearby Tilian Farm Development Center, a farm incubator, to connect growers with Klingenberger’s pickling operations.

Food hubs are extremely diverse in terms of the types services they provide and the markets they serve. According to Richard Pirog, senior associate director of the Center for Regional Food Systems at Michigan State University, no two food hubs are alike. MSU leads a Michigan Food Hub Learning and Innovation Network to coordinate opportunities and share best practices with hubs across the state.

“Besides aggregating and distributing, some hubs provide services that farmers and consumers can use,” says Pirog. “Some provide technical assistance, accounting services, or coordinate food safety training. Some are looking at ways to provide training for new farmers. Some services are revenue-generating, and others are maybe grant-based to work with local food banks to improve food access.”

What unites food hubs is their commitment to building the local food economy. “Their biggest value statement is supporting local farmers and sourcing products locally,” says Pirog. “They are about enabling people to get local food within their communities and keeping money in the community.”