They Came, They Cooked, They Conquered

Italians Settled in Detroit in Search of Better Lives

UBI PANIS IBI PATRIA.

The Latin for “where there is bread, there is my country,” well describes how Italian immigrants made Detroit home, suggests Armando Delicato, author of Italians in Detroit.

“Food and its consumption are the center of Italian-American culture in Southeast Michigan: Where it is grown, where it is sold, how it is prepared and how it is consumed are rituals that give satisfaction to Italian-Americans,” says Delicato, a child of Italian immigrants who settled in Detroit more than 80 years ago.

The story of Italians in Detroit goes as far back as Detroit itself, when Antoine Cadillac founded the city.

“Cadillac’s righthand man was Italian— Alphonse de Tonty,” says Italian Consul Allegra Baistrocchi, adding that almost since the beginning Italians have played an integral part in feeding Southeastern Michigan. “The Italians came and that was the sector they were in. Why was it? Italians know food.”

Early immigrants grew much of their own produce and, in many cases, were the ones to sell produce at Eastern Market and from horse-drawn wagons making deliveries to neighborhoods. Detroit even had Italian eateries by the late 19<sup>th</sup> century, primarily to serve immigrant men who came to the area alone, staying at boardinghouses or with paisanos until they had enough money to send for their families or to return to Italy. Detroit’s Roma Café was one, initially opening in 1888 to serve boarders who would stay the night to work at the market. It became a restaurant in 1890.

For those whose families were already here, Italian women would spend most of their days preparing food for their families while the men would make their own wine in their basements, says Delicato. Being a good provider— especially in regard to food—was important to the Italian-immigrant patriarch.

“He provided the means to survive in America and would often remind his family that in America, unlike the Italy they had left, there was always an abundance of food that would include meat as often as they pleased,” says Delicato, explaining that many of the early Italian immigrants were former sharecroppers in search of better economic conditions. “That’s why they came here: They were hungry.”

Sundays meant visits from extended family who arrived for pranzo (lunch) and stayed through cena (dinner). “Celebrations for the working-class family would usually take place in the home, where the women would begin cooking early in the morning. Family meals were almost a religious event— not to be missed without an acceptable excuse,” says Delicato.

Unlike cities like Cleveland and New York, Detroit lacks a “Little Italy,” other than Windsor’s Erie Street neighborhood. That wasn’t always the case, says Delicato, who describes the area near Eastern Market, where Gratiot Avenue meets Riopelle Street, near where Black Bottom and Paradise Valley stood, as one.

“Lombardi Foods on Gratiot Avenue adjacent to Gratiot Central Market was the main source of imported products from Italy, long before supermarkets provided the wide range available today,” he says. The names of Italian descendants still dot wholesale food purveyors’ warehouses and trucks around the market.

Italians also settled on Detroit’s west side, not too far from the Detroit Produce Terminal or the Ford River Rouge factory, where only traces of the old neighborhood still exist with places like the Original Gonella’s sub shop, which opened more than 75 years ago, and nearby Giovanni’s Ristorante, which opened 55 years ago.

By the 1950s, Italians dispersed, leaving Detroit to head east, with pockets settling in areas of Macomb County, or westward to Dearborn, Livonia and Canton communities.

“The Italians spread out. They moved out to get the white picket fence and the lawns—the American dream,” says Baistrocchi, suspecting it was also to have more room to grow their own food.

“You could just drop us in any of those [cities in Italy] and we would be a successful restaurant, and you can’t do that with a lot of the red-sauce places.”

Today, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates Metro Detroit has 500,000 Americans of Italian descent, says Baistrocchi. “That’s a lot.”

In time, Italian restaurants became more Italian-American, with dishes derived from Italian originals, but serving sizes, ingredients and styles more American than Italian.

“People think spaghetti with meatballs is Italian, but it’s Italian-American,” says Baistrocchi. “It happened in New York. It didn’t happen in Rome.” Alfredo sauce, on the other hand, was invented in Rome, but for American clientele, she says. “You don’t find Alfredo sauce anywhere else in Italy.”

“There’s nothing wrong with Italian-American food—it’s delicious—it’s just not authentic,” says the fourth-generation diplomat from Rome, who is also a trained chef. “We have meatballs in a million and one different ways, but we wouldn’t have pasta next to it.”

In recent years, new Italian restaurants entered the local mix, including Mangiabevi in Sterling Heights, Testa Barrá in Macomb Township, and SheWolf Pastificio and Bar, along with the recent addition of Mad Nice, in midtown Detroit.

“We consider ourselves ‘modern Italian,’” says Anthony Lombardo, chef and co-owner of SheWolf, who sought to create a restaurant that could just as easily exist in Bologna, Milan, Rome or Turin: “You could just drop us in any of those [cities in Italy] and we would be a successful restaurant, and you can’t do that with a lot of the red-sauce places.”

Lombardo doesn’t fault the old-school Italian spots.

“Italian-Americans didn’t have the same ingredients they had in Italy. They had to flex and use what they could find. And just like everything in America, everything gradually became bigger, especially portion sizes,” says Lombardo, who was raised in Sterling Heights and attended culinary school in Italy. “I come from an Italian-American background and I kind of reconnected with my roots by moving to Italy and learning about cucina italiana.”

Roman cuisine continues to inspire him today at SheWolf, named for the Roman myth about a she-wolf that rescues the abandoned twin infants Remus and Romulus, who went on to found Rome.

“Our name and our concept came about in all of these parallels between Rome and Detroit, the rise and fall. Rome fell, of course, and then rose again and Detroit’s going through a similar renaissance. And the amount of pride people feel—Romans are very proud; Detroiters are very proud.”

A Beloved Bakery

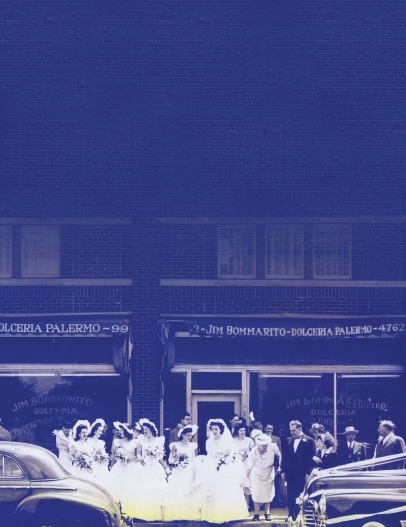

IN 1934, when many Italian immigrants went to work in the automotive or construction industries, Jim Bommarito and his wife, Rose, joined his two brothers selling cookies, cakes, gelati and Italian ice at Joseph Campau and Mullet in Detroit.

Soon thereafter the young couple opened Jim Bommarito Dolceria Palermo, about two miles east at Cadillac and Forest streets. After their daughter, Grace, married Sam Valenti in 1946, the pair would help out on the weekends. In 1960 the Valentis broke ground on a new location in St. Clair Shores—expanding the bakery’s business to include bread, pizza, muffuletta and more.

“My dad was the innovator,” says Christine Corrado, one of the Valentis’ four daughters—along with Roseanne Valenti, Grace Adams and her husband, Eric, and Frances Cottone— who all run the business today.

The sisters practically grew up in the building, says Corrado, recalling how her mother cooked shift meals for the staff, served on long wooden tables the bakery still uses. After so many years in business, they’ve become close with customers, even attending weddings.

“Our patronage—so many have become family. That part of it pulls on our heartstrings.”

Learn about the courses of an Italian meal from Allegra Baistrocchi, Italian Consul in Detroit, on page 6

Learn about pasta-making from SheWolf’s Anthony Lombardo on page 16

Learn more about Roma Café on page 25

Learn more about Giovanni’s Ristorante on page 26

Cara Catallo is editor of edibleWOW and author of Pewabic Pottery: A History Handcrafted in Detroit and Images of America: Clarkston.